Book Excerpt: "Samsara"

This excerpt is taken from Chapter 2 of Holindrian & The Human Revolution

This scene is called Samsara (Saṃsāra) and is taken from the Sanskrit word which speaks to the idea of cyclical death and rebirth. A cursory Google search will say that Samsara refers to reincarnation, karmic cycle, and a cycle of aimless drifting or wandering. While those specific concepts themselves are not found within the story and philosophy of Holindrian, the idea that there are cyclical aspects to human nature--and, by extension, human civilization--is very much central to the lore of this world I've invented.

Before I had ever heard of Graham Hancock and his work postulating the (potential) existence of older, lost civilizations predating the Sumerians and Indus Valley scattered across the globe, the possibility that in all the time human beings have been around that we were the totality of civilization seemed ripe for exploration. Subtracting what can be substantiated in the archeological record (some 10,000 years) from the amount of time modern humans have existed (about 300,000), the idea always seemed, to me, perfectly plausible. Why shouldn't one or more other civilizations have arisen in that time? I don't think any other humans have previously overcome gravity with the invention of flight or harnessed the power of the atom or set foot on the moon, but to reject the possibility out of hand that humans elsewhere over the course of many thousands of years did not come together, establish a community, invent rules to mitigate conflict, make discoveries, practice rituals, and satisfy artistic pursuits seems the more preposterous thing to do.

For this reason, this scene, Samsara, depicts Holindrian (known as Maramurru at this point in the story) and his siblings, having witnessed yet another civilization destroy itself, vow to never let another apocalyptic end befall humanity....

Samsara

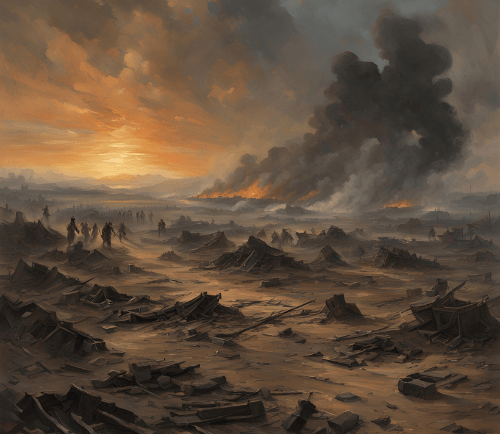

And so, the Fifth Age came to a somber end. Wrecked down. Its foundation collapsing upon itself, weighted down by centuries of moral decay and horrendous war. Huge swaths of land yielded to the raging fires of industry where dilapidated concentrations of man and wealth tempted more envious men to plunder their riches, first by way of the forked tongue and later by force of arms. In their defense, they retreated inward, deeper into the depravity that had long since betrayed them to a damning fate of self-destruction. When the war came, the last war, the tragedy was complete. A dense and suffocating dullness settled in, a grayness that rained down on the bodies stacked up one on top of the other in the network of trenches spanning thousands of miles. Where the fires and pestilence did not kill, the gas, the sickly, pus-colored clouds of chemical contaminants, blew steadily across the continents, leaving the cities in a dark silence from which they would never recover. Anarchy, the ultimate dissolution of society, was the reality the survivors, the cursed few there were, vacating their shelters to find their world had ended.

A student of history would note here that the ending of the Fifth Age exhibited more than one parallel with the destruction that had brought about the Exodus. A cynical observer might note that as proof, positive that sons and daughters are doomed to repeat the mistakes of their parents. A realist would argue that history has taught us that only through our strength might we ever survive the follies of our collective character, while another would look to the same set of facts and conclude it was precisely that flawed logic of the past that would surely again ruin the future. Neither these nor other lessons were absent from the Baltutu, who, after having witnessed yet another collapse of civilization, resolved to act.

The winds were generally still. A feeble breeze was swept up from the south, swirling around the town square, circling the edges and faces of the facades of the bombed-out halls of law and order. The fires had reduced themselves to but a handful of stubborn embers, puffing out smoke like one chewing on the end of dying cigar; clumps of spent fuel remnants huddled round like vulture nests. It was nearly midday, though with the blanket of gray draped over the planet, one might have thought it a later hour. Save for the six cloaked figures trespassing, the square was a fairly silent, undisturbed grave.

At what had not so formerly been both the center of the square and the city itself was a tree, or more precisely now, the blackened charcoal remains of an ancient elm tree. Far and away the city’s oldest inhabitant, its branches had extended out towards the building faces that surrounded it, where the leaves, a rich, vibrant, well-watered green, would push and tickle the fired brick. Those leaves were gone now. The branches, the lot of them, consumed by the fires that had raged. All that remained standing, raised slightly upon a knoll, was the solid, knot trunk—a monument to sin.

“It’s happened again,” said one of the figures scraping a layer of soot from a scorned ceremonial shield with the sole of his boot.

“Before… wasn’t as bad. Not as bad as this,” another remarked, kneeling over the decaying bodies of a presumed mother and father clutching between them their child, trying to protect them from the fire storm.

“Each end is more terrible than the one that preceded it,” this time, the voice was that of a woman, her hair was covered beneath the hood of her cloak, thinly veiling her from sight. “Apsu, we have to do something. We’ve stayed silent for far too long.”

The one named Apsu, who was now tracing his fingers along the face of the child, took a moment to respond. Their bodies had adopted a texture more akin to weathered stone than flesh, hard and callus. Rising, he wrapped himself tighter beneath the folds of his traveling cloak.

“Ours is to guide. What would you have us do?

“Lead them.”

A response came not from Apsu, but the man who had spoken first. A response that was as much a declaration as invocation of a revelation.

“It’s plain that our guidance has fallen short of desired end—yet again.”

Sitting on the sunken steps arranged around the tree, head craning to the side, fingers intertwined, a third man of the group gently shook his head. “Lead them? Or do you mean to rule them, Anshargal?”

Anshargal wiped away the ash settling on his upper lip. “Look around you, Maramurru, have you seen destruction such as this? In all our time on this earth, have any of us been witness to anything like this? No! No, no, we have not because there has never been destruction such as this here.”

“We can’t. We do not rule—”

“We have stayed the course! For 3,700 years we have stayed the course.” Anshargal became increasingly animated, the world was his courtroom, the square his evidence. “We have stayed silent and allowed them to slaughter themselves in droves. We are complicit in their crimes, and their atrocities.”

“You’d have us abandon our responsibility!”

Darting from his position on the steps, Maramurru moved to where Melammu stood, near a pitiful dribble of acidic water leaking from a punctured lead pipe. Reaching into Melammu’s knapsack, he pulled from it the Baraggal, an inscription upon a small metal tablet, encased in a sheet of glass, which only showed itself with the touch of flesh. Pressing his palm against the glass, the tablet illuminated with light, displaying the words of their bond.

Maramurru read the words aloud, his voice reverberating towards heaven: “They will strive to emulate your example, to profit by your views and your wisdom. They will stumble. They will struggle.”

“I know the words as we all do. But Maramurru, you must surely see that we have given them no example to profitably emulate. We have stayed shrouded, living behind masks, working through anecdotal mysticism. We share fables and bedtime stories. Now… there is no one alive to remember those stories. Remember the words of the Enkirus recounting the last days of Erestu. Are they not as fitting, more fitting here? They are, just as our ancestors, destroying themselves and this world.”

“Eridu is not Erestu,” said Maramurru, eyes still fixed on the ancient text.

Anshargal took this moment to ease towards his brother, placing his hand around his shoulder. “No… but it is becoming more and more like Erestu. The home we lost. The home we never knew. We have the opportunity and the capacity to change this world,” their eyes locked, “but, do we have the will, Maramurru?”

The others, who had largely been silent, turned their eyes to Maramurru. They had not needed to contribute. This was not a debate new to them, nor was it unknown to him where the others stood. For quite some time, Anshargal’s words had swayed all but Maramurru. In looking around, absorbing the indiscriminate plague of death, he felt his resolve begin to waiver. If he was honest with himself, it had been wavering longer than he was proud to admit.

He then felt a tug, Shi, the youngest of them and perhaps the most innocent, kneeled her fine robes into the black, while wrapping her milk white fingers on either side of his face. His face frozen in time, auburn hair wind swept, and bronze skin kissed by many suns. Only his eyes showed any signs of age, but even they seemed to smile, silver though they were, from the corners, as though the muscles had become permanently fixed in that position staring down over a nose whom genetics had affixed a small bulge, right there in the middle. Shi, by contrast, was composed of porcelain, her features finely sculpted and sharp, particularly her nose. With brilliant blue eyes that seemed to glow accented by dark eyebrows. Objectively, she was the fairest of the sisters.

“Each of us have our own gifts, our own strengths. Yours is wisdom. If we’re to do this, we’ll need your wisdom more than ever to guide our actions. Ensure fealty to our sacred obligation. We can still save them. Will you save them with us, brother?”

Her words, true to her name, pierced his soul, striking a chord with his conscious. Given the abhorrent manner with which the Fifth Age had ended—murder of tens of millions—the essence of what the others called on Maramurru to do was not lost on him. How could it? Nothing was so apparent; not even the existence of the suns in the sky could be said to be more evident than the state of humanity. The course had to change. It must. But, for all of his countless centuries, the cavity, the singularity that enveloped his heart obstructed any clarity that might have still clung to the recesses of his mind. Racked with such immeasurable grief, for though he did not know the names of the persons who laid dead at his feet, he did know the dreams they had had for themselves, their children, their children’s children. Racked with such immeasurable grief, for though he did not know the nature of their character, he had loved them. He still loved them.

Seeking approval from Apsu, Anshargal removed the Baraggal from Maramurru’s hold, and returned it to the care of Melammu, who stored it once again. “If we are to go through with this, we must abide by the laws we set for ourselves. This decision, like all others, must be unanimous.”

Apsu exposed his face from underneath his hood. His was a face whose skin was stretched tightly against the bone. In addition to being the largest of his kin, he appeared the most alien, with exaggerated limbs but stubby, knotted appendages.

“As eldest among the immortals and the first charged with our solemn responsibility, I call on each of you to declare yourself before one another: Shall we assert ourselves in the coming age to lead mankind according to our purpose?”

“I, Mummu, second born daughter, do declare.”

“I, Melammu, of inspiring light, do declare.”

Maramurru felt Anshargal caress his shoulder as he spoke the words into his brother’s ear, “I, Anshargal, prince of heaven, do declare.”

“I, Shi, breath of life… do declare,” she said, turning to respectfully face her elder.

“I, Apsu, one who exists from the beginning, do declare. What say you, Maramurru?”

The weight of the stock he felt barring his neck was enormous.

“If we do this, we do it for them and not ourselves.”

Apsu craned his head down whilst towering above. “What say you? How do you declare?”

He felt shackled to the spot.

“Yes! Yes…” each word felt to him as a betrayal of the greatest magnitude, worthy of all the lashes a strong man might bring to bear.

“Say the words,” he heard Mummu, almost in a motherly tone, he thought.

Wrenching himself free, he stood before the dead elm, atop the bodies of the inglorious dead, and pleaded as much to the Aeternam as to his brothers and sisters, “I, Maramurru, son of the West, do… declare!”